One thing I have observed, and have come to understand, in my five years of working with dairy farmers, is that they have incredibly busy schedules! They almost always have a subtle look of exhaustion whenever I interact with them. I suspect this is mainly due to how demanding their job is, both physically and mentally.

One thing I have observed, and have come to understand, in my five years of working with dairy farmers, is that they have incredibly busy schedules! They almost always have a subtle look of exhaustion whenever I interact with them. I suspect this is mainly due to how demanding their job is, both physically and mentally.

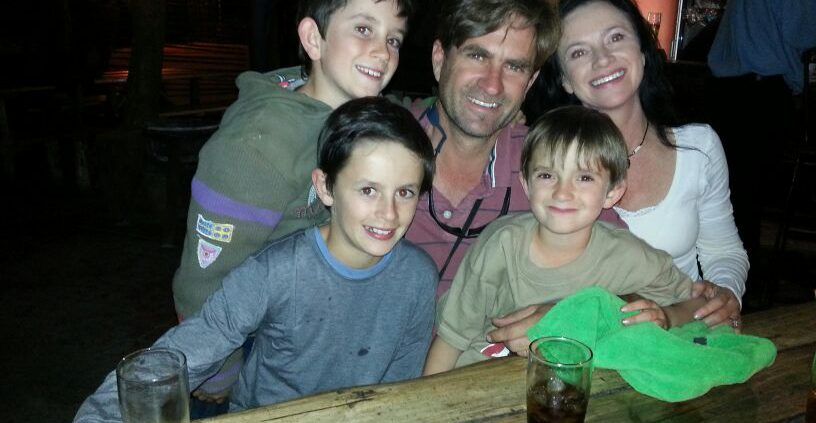

I once asked a farmer if he loves his work, his response to me was, “Hate it, but wouldn’t change it for the world”; which I found to be quite hilarious. Rufus Dreyer (RD) is one of those few people who pack 30 hours of work into a 24 hour day. That is the only explanation I could come up with to rationalise how he is able to manage a farm efficiently, fly aircrafts and take up photography as a hobby, none of which are easy to do.

Having been in the dairy industry for just over 10 years, Rufus Dreyer is one of the early adopters of sustainable dairy farming practices in the area. He runs a farm just outside Humansdorp, close to Oyster Bay. He is a modest individual who is always keen to share his knowledge and experience of farming with young people and emerging farmers. Rufus loves the outdoors, and it is no wonder why nature is his favourite backdrop for taking photographs.

Some of the beautiful photographs taken by Rufus (See more in gallery section)

I caught up with Rufus to find out where his journey with farming started and many other things.

PP: When did you start farming and did you grow up on a farm?

RD: In 1993, first with stock farming on our family farm in Adelaide, after the sudden death of my father, and then dairy farming in 2004. Yes, I grew up on a farm.

PP: Why did you want to become a farmer?

RD: The exposure I had as a child pushed me in that direction. It made sense since my dad was a farmer already, and in a way, it was “expected” of me to take over one day.

PP: Are there any differences between your farm now and your farm when you were a kid?

RD: Yes, less staff, more pressure to make a living on an economical unit that has shrunk due to inflation, and farming practices that have become less profitable. Infrastructure has also deteriorated due to lower margins and a lack of money for maintenance.

PP: What is the biggest change that you have encountered during your years of farming?

RD: Laws regarding labour, like maximum hours allowed per week, and security of tenure, as well as the introduction of unions. Land that belonged to my family for over 100 years was expropriated due to politics. Agricultural services have ceased to exist, as well as the seizure of subsidies from Government. The government does not value the SA Farmer and the importance of their role in job creation and providing food. It has forced farmers to be more independent and self-sustainable, and by this has raised the bar for those that want to enter the farming industry.

PP: How have advances in technology, such as machinery, genetics, or chemicals, affected your farm? You can give an example

RD: Various farm computer programs have put me in a position to keep better records and enabled me to analyse my business better and make better decisions. We used to do irrigation on a small scale by flood, perrit pipes, and draglines. We now use pivots for much bigger areas, with better water use, controlled by internet or cell phones. Cell phones themselves have made a huge difference in running our business better.

PP: Have you observed changes in the number, size, and type of farms that are found in your immediate locale? What is your attitude toward any trends you may have noticed?

RD: Economical units are getting bigger; therefore the successful farmers buy out the less successful farmers. There are less people in rural areas, owning more land. Farms are also often bought in big partnerships, with investment from the private sector.

PP: In another world, where you were not a farmer, what work do you think you would do?

RD: Engineering, Architecture, Veterinary.

PP: What are the most difficult and most satisfying aspects of farming for you?

RD: The most difficult is the effect of climate, and especially rain, or the lack thereof. There are many uncontrollable variables in farming, which makes it very challenging. We farmers always seem to be price-takers, and often have little control of how our products are valued. The most satisfying is probably to see the reaction of nature to good rains and to observe stock in good condition grazing quality pasture or veld.

PP: What advice would you give to any young person interested in getting into farming?

RD: Identify a good farmer and find a way to learn from him to get experience. Work for such a farmer for “nothing” to help you start your career. I believe that if such a farmer sees your willingness and passion for farming and the potential in you then doors will start to open for you. I also believe that even if you have it all cut out for you, you, for example, will take over your family farm one day, you have to work for at least one “boss” before you become one. Good decisions come from experience, and experience comes from bad decisions. Nobody can ever take the experience away from you.

Often young people (myself included, before being exposed to farming) would think farming is easy as 1, 2, 3, but a lot of hard work is done in the background. A farmer has to play the role of an administrator, economist, agronomist and nutritionist, all at the same time. Hence, the point made by Rufus about finding a farmer to shadow is of such significance. Our university degrees/diplomas only teach us about the theory behind farming, but not the practicalities around it, which I believe are the most important.

- The management of soils with excessive sodium and magnesium levels - 2023-06-12

- Understanding evapotranspiration better - 2021-10-18

- Soil fungi connections - 2021-09-28