Many dairy farmers in South Africa are very progressive. In my experience, farmers have done well to push for greater efficiency in their systems. It could leave some people asking, is there still room for much more improvement? My answer, absolutely!

The challenge of sustainability

Sustainability is not something that can be achieved and then you sit back. It is a constant pursuit of ensuring long-term profitability, reducing environmental impact and being socially responsible. It is an ever-evolving goal.

I am looking at the question of what is possible in the future for pasture-based dairy farms through the lens of sustainability. Most importantly, for this article, I want to focus on the influence that reduced input costs has on long-term resilience. Reduced input costs mean a farmer is less subject to availability and cost of feed, fertiliser, electricity, and fuel. Not only do reduced inputs lead to resilience, but also reduced environmental impacts. The production of these inputs has associated greenhouse gas emissions, as do the use of fertiliser and fuel.

Reduced inputs sound great, but I am sure the question you are all asking is, what about production? Well that is a good question.

Optimising production

One of the points I always like to emphasise about sustainability is that it is about optimising production, not maximising it. The problem with optimising is that it differs between contexts, and therefore from farm to farm. There is no one formula for figuring out how to optimise production with any given set of inputs. This is something each farmer must figure out for themselves.

That said, what we can do is look at some of the principles which assist in the optimisation of production. The main ones I will focus on in this article are:

- Improving soil health – healthier soil supports more abundant and better-quality pasture growth, with lower fertiliser inputs.

- Improving pasture quality – improved pasture quality supports higher milk production, and a higher percentage of pasture in the total diet, i.e. better-quality pasture leads to a smaller need for concentrates.

- Decreasing heifer replacement rates – a decrease in the number of heifers required to replace culled cows each year results in a need to rear less heifers, where an emphasis can be placed on optimally rearing only the best heifers.

Levers

There are many factors on a farm which farmers have no control over. This includes the weather, the milk price, and the prices of concentrates, fertiliser, fuel, and electricity. Although these are things farmers need to be aware of, it is pointless agonising over them. A farmer’s energy is better served focussing on things which they can control.

These include the principles which I mentioned above. You could think of various management practices on a farm as levers. When these levers are applied according to the principles, production is optimised. For example, by implementing no-till practices, multispecies pastures, smart fertilisation strategy and ideal grazing management, soil health and pasture quality can be improved. Another example is that by improving herd management that leads to healthier animals, therefore greater longevity, and by obtaining higher fertility rates, lower heifer mortality and better heifer rearing the number of heifers needed each year can be reduced.

The impact of applying these levers

I would like to use a theoretical farm in the Tsitsikamma as an example of the impact that applying the levels in the correct way can have on the sustainability of a farm. I have created a model farm based on averages of data from 23 farms on the Trace & Save database. These are all mixed irrigation and dryland farms.

I have used four different scenarios, where the levers discussed have been applied to different extents. The first scenario is a relatively normal, productive farm under current circumstances. The other three scenarios show the effects of some big changes to the way pasture-based dairy farms are thought about and managed. The three are categorised as conservative, progressive, and ultimate in terms of the level to which these changes have been implemented.

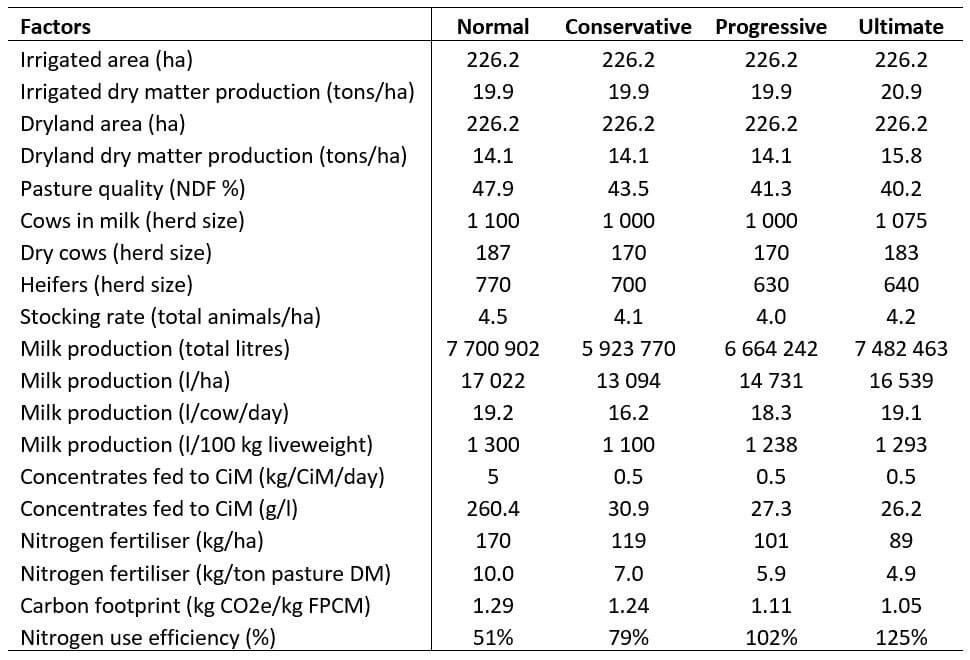

The four scenarios have been laid out in Table 1 below. Factors which were kept constant were the size of the farm (452.5 ha), the size of the cattle (450 kg cows in milk), butterfat (4.4%), protein (3.6%) and the type of inputs used. Everything else was subject to the changes brought about by applying the various levers.

Table 1: Four different farm scenarios, showing the impact of changes in management practices

Fundamental change in thinking

The two most important changes in these models were the absolute minimisation of concentrates, and the reduction in nitrogen fertiliser. Most farmers will probably look at the concentrate and nitrogen figures and say that these milk productions and pasture growths are not possible under these scenarios. And I get why you would say that – these figures have never been achieved. But they are theoretically possible.

The feed provided in these scenarios is sufficient to support the milk productions mentioned. The caveat is that the pasture quality needs to be at the specified levels. To achieve that we need high quality, multispecies pastures.

We also know that these levels of pasture growth are possible with such low fertiliser inputs (Growing pasture with minimal nitrogen fertiliser). The caveat here is that we need healthy soils to achieve this. Practices which improve soil health should be prioritised.

The challenge is then to take advantage of improved soil health. This is where I think many farmers still have a mental block. To achieve this level of progress, we need to change the way we think about fertiliser and the way we manage pastures. It is a huge mental shift.

To achieve these levels of production using such low concentrates it is also imperative that we calculate stocking rates intending to maximise pasture intake. Conventional wisdom says that a cow can take in 1.2% of their body weight in NDF each day. We have found this factor to be closer to 1.5%, especially in smaller cattle. For this exercise I used 1.4% and stocked the farm so that cattle would eat the maximum amount of grass (and silage) every day. By improving pasture quality, therefore reducing the NDF and increasing the energy, cows can eat more pasture and produce more milk from pasture.

The changes mentioned above were the basis for the change between the normal and other three scenarios.

Going beyond the fundamental change

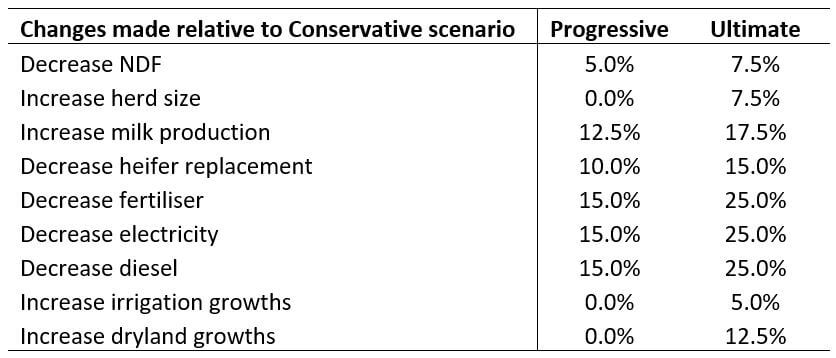

The progressive and ultimate scenarios require a huge leap in thinking and practices from the current convention. Table 2 shows the changes that were incorporated in the model between the conservative, progressive and ultimate scenarios.

From the normal to the conservative scenarios, focus was placed on increased pasture quality (i.e. decreased NDF) and improved soil health (i.e. decreased fertiliser). The other big difference is in concentrates fed. The goal of this exercise is to fundamentally challenge the current thinking on dairy production. The biggest variable costs on dairy farms is concentrates. By feeding minimal concentrates (i.e. 0.5 kg/CiM/day), this completely changes the dynamic of current thinking.

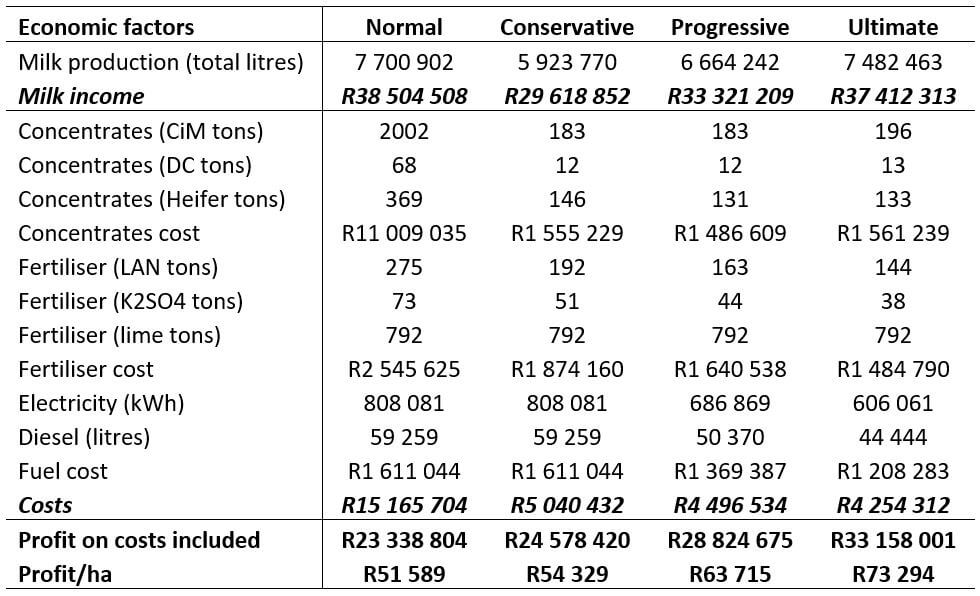

The impact of feeding such little concentrates under the conservative scenario is that stocking rate and milk production must decrease. Table 3 below shows the impact this all has on the profitability between the systems. I know many farmers who would still choose the normal system, because it has higher production, but the conservative system is more profitable per hectare. I understand that the real world of dairy farms is a lot more complex than this, but I think this should give farmers something to think about.

Table 2: Changes in factors between the conservative scenario and the progressive and ultimate scenarios

When we start considering the changes made to get to the progressive and ultimate scenarios, it creates what I hope dairy farmers would find an interesting, and exciting prospect. The key is the further improvement in pasture quality (i.e. decreased NDF). The lower the NDF gets, the greater the pasture intake. This initially supports increased milk production (progressive scenario) and then supports increased stocking rate as well (ultimate scenario).

The change in heifer replacement is linked to what was discussed above with regards to improvements to herd management. This is necessary to contribute to the increase in cows in milk, and therefore increase in milk production per hectare.

The change in fertiliser, with an associated increase in growths under the ultimate scenario, is associated with improved soil health. This is the part that will take concerted, consistent effort and focus from farmers to get right. It is also something that needs to be earned on a farm, it will not happen overnight. Improved soil health means a thriving, balanced soil food web which efficiently cycles nutrients in the soil. It also means a balanced soil fertility, linked to the thriving soil life. Further to that, it means a well-structured, aerated soil which allows for movement of air and water, creates ideal habitat for soil microorganisms and allows for easy root growth and development. Achieving this level of soil health will drastically decrease a farms reliance on fertiliser. It will also lead to an increase in consistent growth of high-quality pastures.

The decreases in electricity and diesel are associated with overall improvements in farm efficiency. Most notably, with improved soil health, irrigation will be a lot more efficient, therefore saving on electricity. A decrease in fertiliser usage will also lead to a decrease in diesel, as diesel for fertiliser is a big contributing factor. Improved soil health should also lead to a general decline in work needed on pastures, for example spraying pesticides and ripping.

The economics

I completely understand that I have not included all the costs on a dairy farm in this exercise, but I have included the most important variable costs. Many of the costs which I have not included would remain constant, or potentially decrease with the more progressive scenarios. Table 3 gives an overview of the income versus costs of the different scenarios.

Table 3: Income versus costs of the four scenarios considered using the model farm

Once again, I would challenge farmers to think about profit per hectare as the most important indicator of economic success. It seems obvious, land is the main limiting factor to growth, and therefore it is the common denominator with which to assess the profitability of an operation. That said, it is so often that I come across an emphasis on total production, or production per cow, or total turn-over as the focus.

Based on turn-over, you would choose the normal scenario, even though this is the least profitable. Based on production per cow, you would also choose the normal scenario. It takes a different approach, and new way of thinking, to appreciate that the conservative approach is better (more profitable) than the normal approach. And the progressive and ultimate scenarios are just building further on this.

It is a process

It should be emphasised that it is a process to reach the ultimate scenario. I do not expect farmers to see this and change their systems overnight. I am challenging farmers to think differently about how their farm systems are set up, especially in terms of their reliance on concentrates and fertiliser inputs. There is an alternative approach to the current convention.

I encourage farmers to assess their current farm system. What are the opportunities on the farm? If you want to move away from the normal, to the more progressive systems, what do you need to change? Where is the best place to start?

Trace & Save can help you with these questions, and with measuring your progress along the way. Improving a farm is a constant, adaptive process. Every farm is different, and the situation is ever-changing. Only by measuring the correct indicators can we identify opportunities and adapt farm systems accordingly.

- A carbon footprint assessment for pasture-based dairy farming systems in South Africa - 2024-02-07

- What progress have farms participating with Trace & Save made over the past 10 years? - 2023-09-06

- Carbon footprint reduction over time: Lessons from pasture-based dairy farms in South Africa - 2023-09-04